TUESDAY, May 29, 2018 (HealthDay News) — Alec Smith was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes shortly before his 24th birthday. When he turned 26, he lost his health insurance. Less than a month later, he lost his life because he couldn’t afford the exorbitant price of his life-saving insulin.

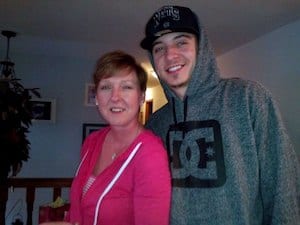

“Alec had a full-time job that didn’t offer health insurance. But because he was working full-time, he didn’t qualify for subsidies under the Affordable Care Act. The insurance he could get, the premium and the deductible were so high, he couldn’t afford to pay for a policy. His deductible would’ve been $7,600,” his mother, Nicole Smith-Holt, said.

When he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, Smith-Holt said, her son was determined not to let the disease change his life. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease that causes the body’s immune system to mistakenly attack healthy insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Insulin is a hormone that helps transport the sugar from foods into cells for use as fuel.

People with type 1 diabetes make little to no insulin, so they must replace the lost hormone through injections or a tiny tube inserted under the skin and attached to an insulin pump. But replacing that lost insulin doesn’t come cheaply.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Bernie Sanders pointed out that a vial of insulin cost about $21 in 1996. That same vial of insulin cost about $255 in 2016. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has noted that Europeans pay about one-sixth of what Americans pay for insulin.

It was the high price that led Smith to try to ration his insulin; he simply couldn’t afford to buy another vial. He didn’t realize that even if someone with type 1 diabetes eats a low-carbohydrate diet (carbohydrates are turned into glucose in the body), they cannot get by without insulin.

On a Sunday night in late June 2017, Smith went to dinner with his girlfriend. He said he wasn’t feeling well and complained of abdominal pain. Abdominal pain is one of the symptoms of a serious and potentially deadly complication of diabetes called diabetic ketoacidosis, according to the ADA. This condition occurs when the body doesn’t have enough insulin.

The next morning Smith called in sick to work. His girlfriend tried to reach him repeatedly on Monday, but had to work. She planned to check on him Tuesday morning. She did, but it was too late.

As Smith-Holt recounted the story, she said her son never asked for help. “I wish he would’ve come to me,” the Richfield, Minn., woman said, but added that he was very independent.

And although it’s hard for her to tell the story of her son’s death, she said, “I’m hoping the story gets out there. Somebody needs to make a change. This can’t continue. More people will die or end up in the hospital. I want to try to save other lives.”

More than 7 million Americans require insulin

Smith-Holt isn’t alone in trying to draw attention to this problem. Two years ago, the American Diabetes Association asked Congress to hold hearings to determine why the cost of insulin was skyrocketing.

Congress recently did just that, and the ADA’s chief scientific, medical and mission officer, Dr. William Cefalu, testified before the U.S. Senate’s Special Committee on Aging.

“Insulin is a life-sustaining medication for approximately 7.4 million Americans with diabetes, including approximately 1.5 million individuals with type 1 diabetes. There is no substitute,” Cefalu said.

He told senators insulin costs about $15 billion a year in the United States. Between 2002 and 2013, its average price tripled, according to Cefalu.

So, why has the price of insulin gone up so dramatically?

Unfortunately, there are no easy answers.

The ADA found there was little transparency in pricing along the insulin supply chain. It’s not clear how much each intermediary (wholesalers, pharmacy benefit managers and pharmacies) in the supply chain benefits from the sale of insulin. It’s also not clear how much manufacturers are paid as this information isn’t publicly available either.

The ADA also noted that the current pricing and rebate system encourages high list prices (that’s what someone without insurance or who has a high deductible is often stuck paying).

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have substantial market power and can control which insulins are approved to be on an insurer’s list of approved medications (formulary). PBMs receive rebates and administrative fees, but don’t have to disclose them. They can exclude insulins from a formulary if their rebate is too low, according to the diabetes association.

People with diabetes — like Alec Smith — are the ones who end up harmed by high list prices, high out-of-pocket costs and formulary restrictions.

“Insulin access and affordability are a matter of life and death,” Cefalu said.

The ADA also had a number of recommendations that Cefalu passed on to Congress, including:

- Ensuring access to affordable insulin for those without insurance.

- Requiring greater transparency throughout the supply chain.

- Doctors prescribing the lowest price insulin to meet treatment goals effectively.

- Keeping rebates, discounts and fees to a minimum.

- More closely matching list price of insulin to the net price that’s paid.

Smith-Holt has some advice for parents of children with type 1 diabetes and those who have type 1 diabetes themselves.

“Speak out. Share your stories. This problem is outrageous and it’s only getting worse. People need to speak up,” she said.

More information

Learn more from the American Diabetes Association about the need for insulin affordability.