WEDNESDAY, Aug. 29, 2018 (HealthDay News) — A drug that has long been used in Japan for asthma may slow down brain shrinkage in people with progressive multiple sclerosis, a preliminary trial has found.

The study, published Aug. 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine, tested an oral drug called ibudilast. It is not approved in the United States, but has been used for years in Japan as a treatment for asthma and for vertigo in stroke survivors.

Researchers found that the drug slowed brain shrinkage by 48 percent when compared with an inactive placebo among patients with progressive MS.

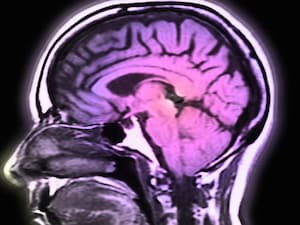

Multiple sclerosis is a neurological disorder caused by a misguided immune system attack on the protective sheath around nerve fibers in the spine and brain. Depending on where the damage occurs, symptoms include vision problems, muscle weakness, numbness, and difficulty with balance and coordination.

Most people with MS are initially diagnosed with the “relapsing-remitting” form, meaning that their symptoms flare up for a time and then ease.

Patients in this trial had progressive MS, where the disease steadily worsens without periods of recovery.

And while more than a dozen drugs are available to manage relapsing MS, there are few options for progressive forms of the disease, said Dr. Robert Fox, lead researcher on the new study.

In general, the drugs for relapsing MS do not work for people with progressive forms, said Fox, a neurologist at the Cleveland Clinic.

The biology of progressive MS, Fox explained, seems to be “fundamentally different.” Inflammation drives relapsing MS, while the progressive forms seem to be driven by degeneration of nerve cells in the brain, following damage from the inflammatory phase.

Ibudilast can suppress inflammation, and it was first tested against relapsing MS — where it failed to prevent relapses. But, Fox said, the drug did slow brain shrinkage (atrophy). And that led researchers to suspect it might help patients with progressive MS.

Fox and his colleagues recruited 255 patients with progressive MS from 28 U.S. medical centers. Patients were randomly assigned to take either ibudilast or placebo pills every day for 96 weeks.

In the end, patients on the drug showed, on average, 48 percent less atrophy in their brain tissue.

The big question, Fox said, is whether that will slow patients’ progression to disability.

“This is a proof-of-concept,” he said. “We’ve shown that this slows brain atrophy. We haven’t shown that it slows clinical progression.”

Longer-term studies are needed to prove that. For now, Fox stressed, “this drug is not available in the U.S., and it will be some time before it is.”

Bruce Bebo is executive vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society — which partly funded the trial.

Bebo called the findings a “milestone,” but cautioned that the drug will have to show benefits against the disease’s course, and not only brain shrinkage.

“Those clinical benefits take a longer time to measure,” he said. For patients and families, though, this is one more positive step against progressive MS, he added.

“This is one of a number of trials testing new therapies for progressive MS,” Bebo said. “It’s only a matter of time before we’ll have more and better treatments.”

Ibudilast did have side effects: 92 percent of patients in the trial reported “adverse events,” though 88 percent of placebo patients did, too. Headaches and gastrointestinal symptoms — like abdominal pain and nausea — were the main problems tied to the drug.

In addition, 9 percent of ibudilast patients developed depression, compared to 3 percent of placebo patients.

Fox said, “That’s something we’ll want to watch very carefully going forward.”

But overall, only 8 percent of ibudilast patients withdrew from the study because of a side effect. That suggests the drug was well-tolerated, Fox said.

There are two forms of progressive MS: secondary, which develops after an initial diagnosis of relapsing MS; and primary, which means it progressively worsens from the start, with no periods of remission.

About half of Americans with MS have a progressive form of the disease, according to Bebo.

Yet, Fox said, they’ve been “underserved” when it comes to research into new treatments.

“Progressive MS has been the forgotten child,” Fox said. “I think this study can provide them with another chapter of hope.”

More information

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society has more on treating MS.