MONDAY, May 28, 2018 (HealthDay News) — Heart disease remains a major killer of the homeless, a new review confirms.

A combination of access to care, predicting who’s at risk, and challenges of managing care all contribute to the increased odds of dying from cardiovascular disease among this population, researchers reported.

“Clinicians need to make a concerted effort to overcome the logistical hurdles to treating and preventing cardiovascular disease in homeless populations,” said lead researcher Dr. Stephen Hwang. He directs the Center for Urban Health Solutions of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto.

“Half of homeless individuals don’t have access to a consistent source of health care, making follow-up visits and lengthy diagnostic tests a challenge. It’s our duty as health care providers to adjust our practices to provide the best possible care for these vulnerable patients,” Hwang added.

The report was published May 28 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The statistics are staggering. Across America, some 550,000 people are homeless on any given night, and between 2 million and 4 million are homeless during the course of a year. Their average age is 50. Roughly 60 percent are men and 39 percent are black.

These groups have the highest rates of death from cardiovascular disease, highlighting the need for prevention and treatment, the researchers said in a journal news release.

Although cases of high blood pressure and diabetes among the homeless are similar to those in the general population, they often go untreated, leading to poorer blood pressure and blood sugar control.

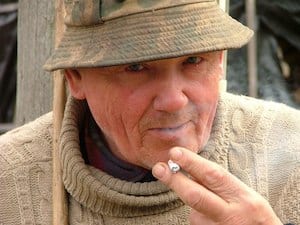

Smoking is the largest contributor to cardiovascular disease deaths among the homeless, the findings showed. About 60 percent of deaths from heart disease are due to tobacco.

Most homeless people want to quit smoking, according to the report, but quit rates are only one-fifth the national average.

Moreover, homeless people are more likely to drink heavily and have a history of cocaine use, the study authors pointed out. Alcohol and drug abuse have been linked to congestive heart failure, atherosclerosis, heart attack and sudden cardiac death.

In addition, one-quarter of homeless people suffer from a chronic mental illness, which contributes to heart disease risk and complicates diagnosis by affecting their desire to seek care.

The researchers also explained that homeless patients are more likely to use the emergency department, which contributes to a cycle of care focused on immediate needs rather than long-term management.

And without health insurance and permanent housing, homeless patients struggle to stay on medication that requires multiple doses per day, according to the report.

“We need to apply evidence-based treatment guidelines for patients experiencing homelessness, and cardiologists can work with primary care providers to help achieve this goal,” Hwang said in the news release.

More information

To learn more, visit the National Alliance to End Homelessness.